Why NUCCA Care Could Be the Missing Link for EDS and Neck Instability

If you live with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), generalized joint hypermobility, or lingering symptoms after whiplash or concussion, you may recognize a frustrating pattern: you’ve tried physical therapy, medications, specialists, and imaging—yet something still feels unresolved.

For many of these patients, the missing piece is not another treatment, but a biomechanical problem that has never been adequately addressed: instability and misalignment at the upper cervical spine, where the head meets the neck.

The Upper Cervical Spine: A Small Area With Outsized Influence

The upper cervical spine—specifically the atlas (C1) and axis (C2)—supports the weight of the head and allows for fine-tuned movements such as nodding, rotation, and balance control. Unlike most of the spine, this region relies heavily on ligamentous stability rather than large muscles.

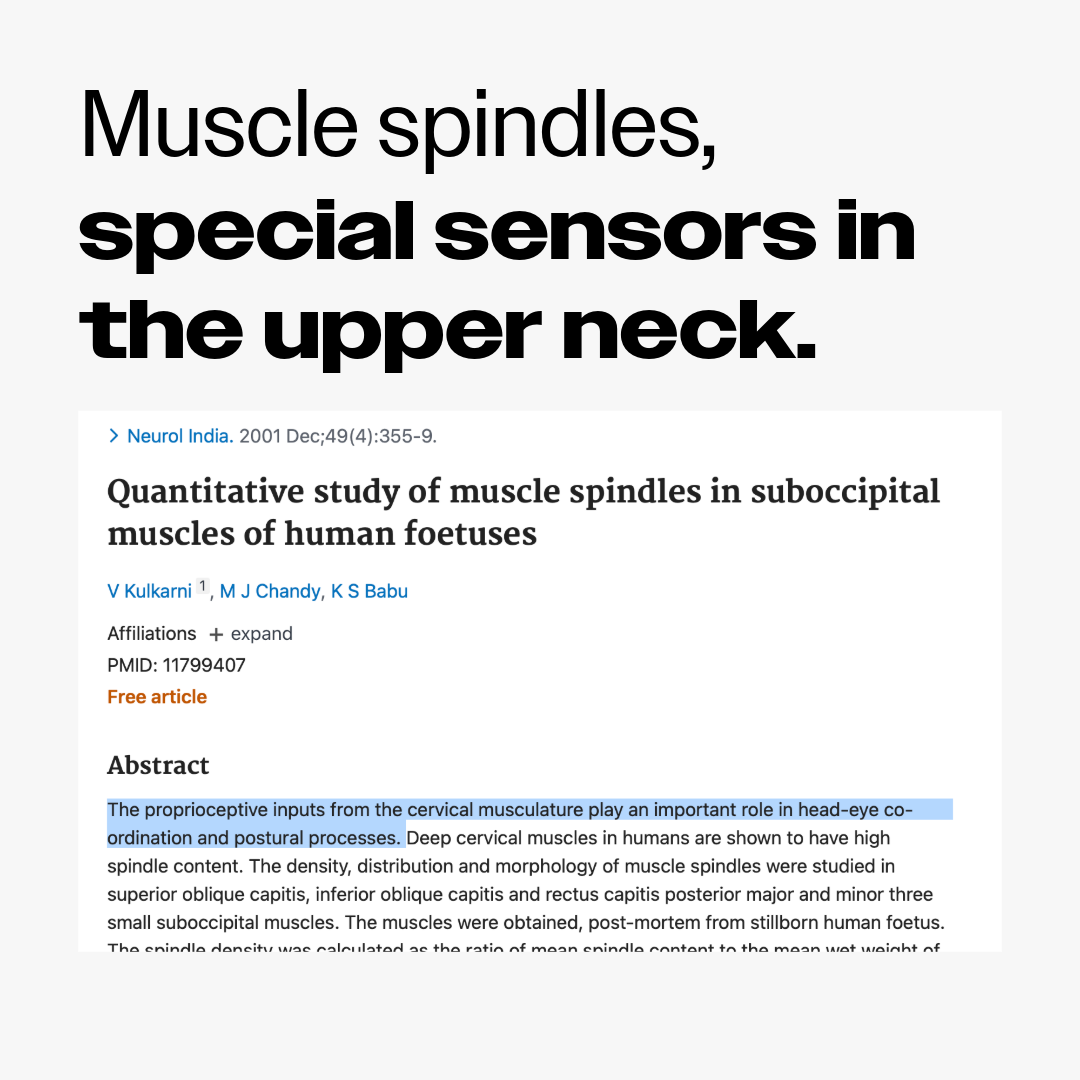

It also sits directly adjacent to critical neurological structures, including the lower brainstem and upper spinal cord, and plays a major role in head-eye coordination, balance, and postural control.

When this area loses stability or alignment, even subtly, the effects can extend well beyond localized neck pain.

Why EDS and Hypermobility Change the Equation

EDS and hypermobility disorders are characterized by connective tissue laxity, often due to abnormalities in collagen structure or function. Estimates suggest EDS affects roughly 1 in 5,000 people, though hypermobility spectrum disorders are far more common and frequently underdiagnosed.

In the upper cervical spine, ligament laxity means:

- Passive stability is reduced

Ligaments that normally limit excessive motion allow greater movement than intended.

- Muscles compensate continuously

Neck and suboccipital muscles remain chronically active to stabilize the head, contributing to fatigue, pain, and tension headaches.

- Neurological tolerance is lowered

Even small positional changes—sometimes within “normal” imaging ranges—can provoke symptoms such as dizziness, visual disturbance, or brain fog.

This helps explain why many hypermobile patients describe a “heavy head,” symptom flares with minor movements, or difficulty tolerating traditional manual therapies.

Whiplash, Concussion, and Why Symptoms Overlap

Whiplash and concussion are often discussed as separate injuries, but biomechanically they are closely related. Sudden acceleration-deceleration forces affect both the brain and the cervical spine simultaneously.

Clinically, this matters because symptoms such as headaches, dizziness, light sensitivity, concentration problems, and visual disturbances can originate from either—or both.

Research has shown that patients with whiplash injuries may demonstrate subtle neurological changes even when standard brain imaging appears normal. This supports the idea that persistent post-concussion-type symptoms may involve ongoing cervical dysfunction, not just the brain itself.

When cervical mechanics remain altered, the nervous system may continue receiving distorted proprioceptive and balance signals, delaying recovery.

Why Standard Neck Treatments Often Don’t Hold

Patients with ligament laxity or cervical instability frequently report that:

- Adjustments don’t “stick”

- Symptoms flare after manipulation

- They feel worse after rotational or high-velocity techniques

- They’re understandably nervous about neck treatment

This is not surprising.

Many conventional spinal techniques rely on rapid movement to break joint adhesion. In a spine that already lacks ligamentous restraint, adding force or rotation can increase irritation rather than restore stability.

What these patients need is not more force—but more precision.

NUCCA Upper Cervical Care: A Stability-First Approach

NUCCA (National Upper Cervical Chiropractic Association) care is designed specifically for the biomechanics of the C1–C2 region.

Key principles include:

- Individualized structural analysis

Precise imaging is used to assess each person’s unique upper cervical alignment rather than relying on generalized adjustments. - Low-force, non-rotational correction

Corrections are delivered with minimal pressure, without twisting or cracking, reducing stress on already lax tissues. - Emphasis on holding, not repeating force

Follow-up visits focus on monitoring alignment and stability rather than routine re-adjustment. - Objective reassessment

Structural changes are verified rather than assumed.

For patients with EDS or hypermobility, this approach respects tissue fragility while addressing a problem that often goes uncorrected.

What Patients Often Notice Over Time

When upper cervical alignment improves and remains stable, patients may report:

- Reduced neck tension and head heaviness

- Improved tolerance to movement and posture

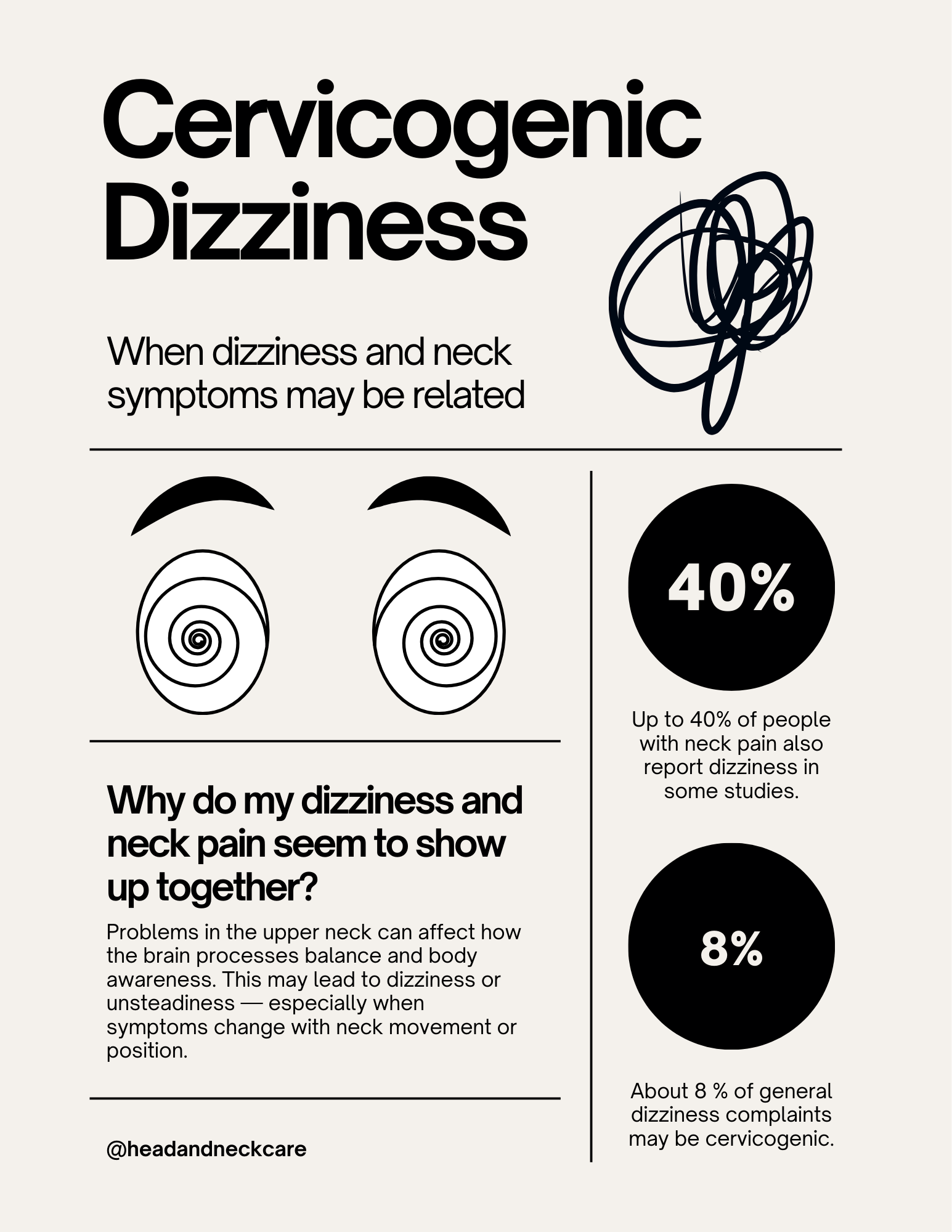

- Decreased dizziness or balance disturbances

- Better coordination between vision, head position, and body awareness

- A calmer, more regulated nervous system response

Importantly, responses vary, and improvement often occurs gradually. NUCCA care is not a cure for EDS or concussion—but for the right patient, it can remove a major mechanical stressor that interferes with recovery.

Who May Benefit From an Upper Cervical Evaluation

This approach may be worth exploring if you experience:

- Chronic neck pain associated with hypermobility

- Headaches or migraines linked to neck position

- Persistent dizziness or balance issues

- Ongoing symptoms after whiplash or concussion

- A sensation that your head feels unstable or overly heavy

- Autonomic-type symptoms triggered by neck movement

- Repeated failure of conventional neck treatments

The Takeaway: Precision Over Force

Hypermobility requires a different clinical mindset. Aggressive techniques often fail not because patients are “difficult,” but because their tissues demand stability-first care.

The upper cervical spine is small, but its role in posture, balance, and neurological signaling is substantial. For patients who have exhausted other options, addressing this region carefully and conservatively can become the foundation that allows other therapies to finally work.

The goal is not constant treatment—it’s lasting stability.